Clear and serene, transcending the passage of time: A Special Feature on Miyanohara Ken

Loneliness Enveloped in Colorful Ceramics

by Sumiko Sugiura, Ceramic Researcher

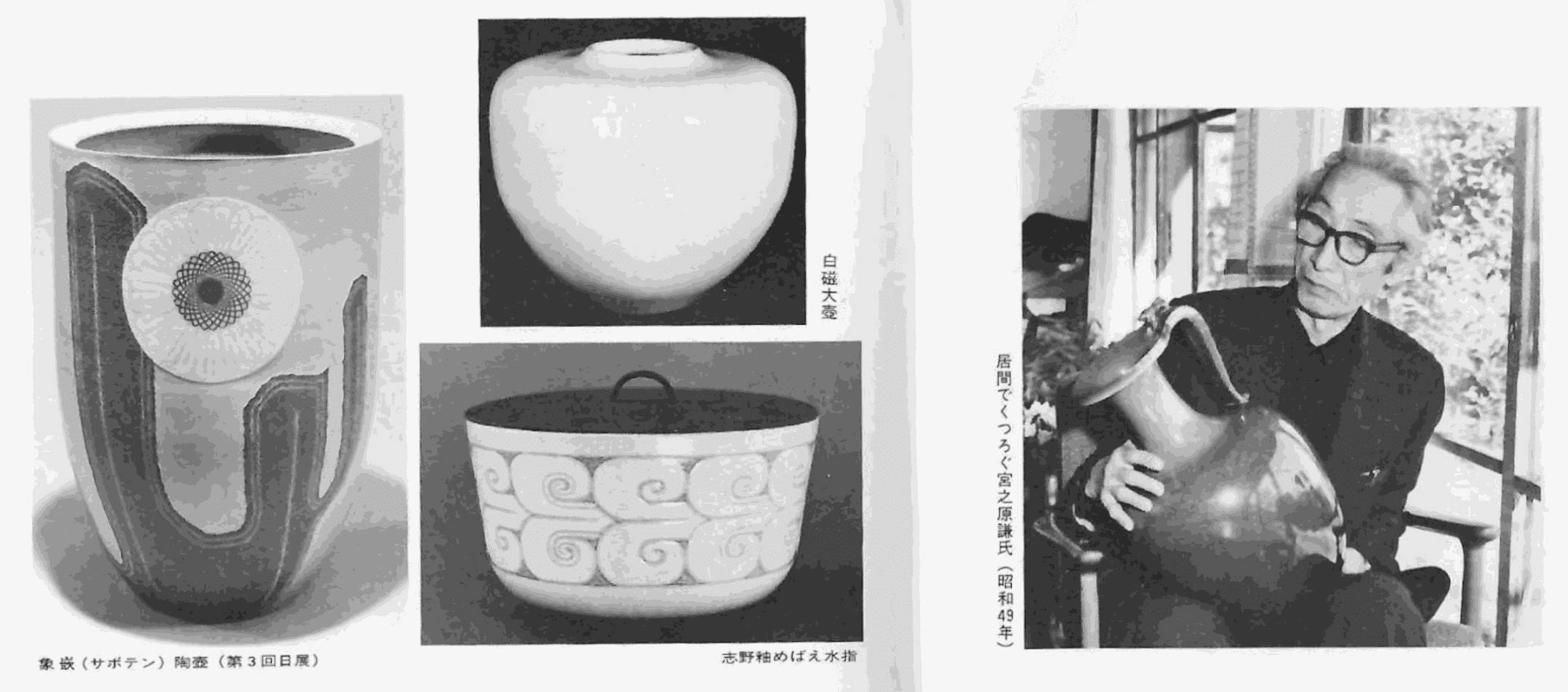

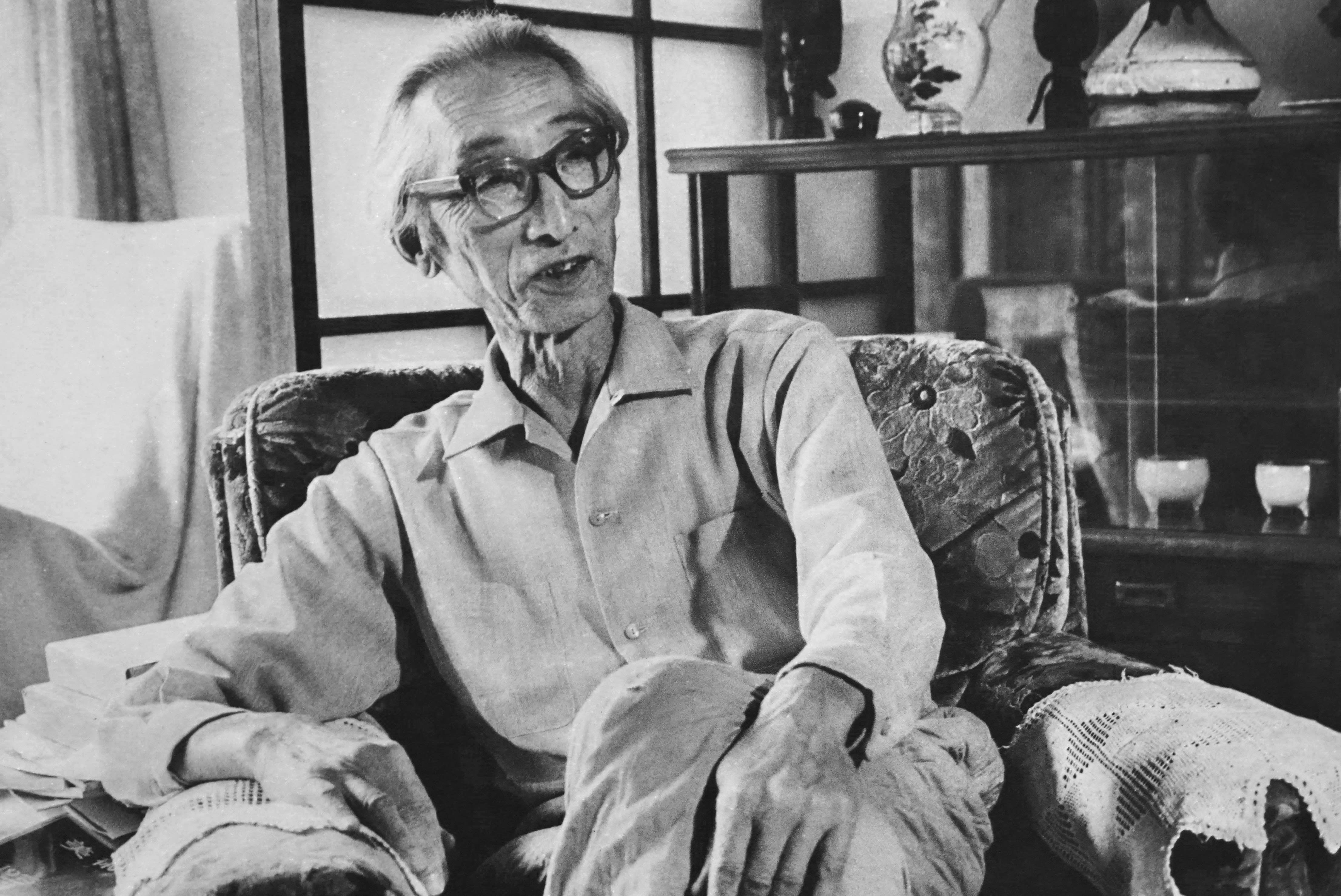

The funeral of Miyanohara Ken took place two years ago on a hot day in August. The residence, located in the outskirts of Matsudo, was indeed that of a prominent figure in the Nitten exhibition, and as a result, the procession of mourners continued for a long time. In the clear blue of the summer sky, I once again remembered the dignified personality ofMiyanohara. He passed away at the age of seventy-nine. My connection withMiyanohara was established in his later years. I had long been captivated by his works, having seen them at the Nitten exhibition and Mitsukoshi's solo exhibitions. Joining the thirty artists in the dialogue with ceramic artists, Miyanohara became the first person I encountered.

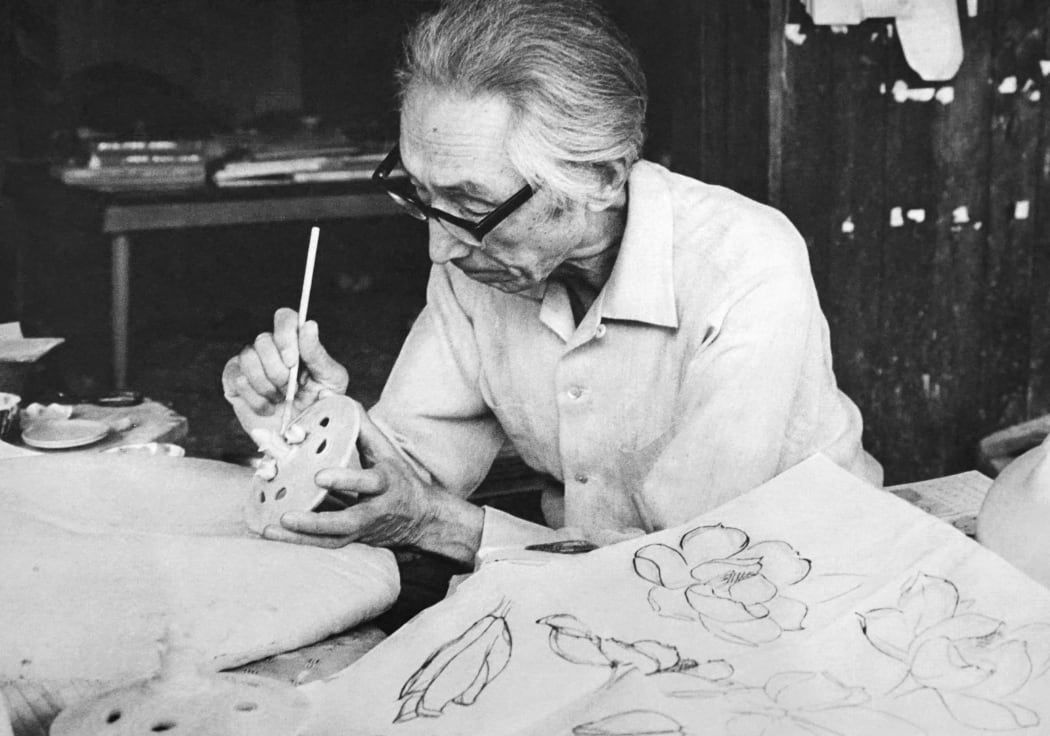

Portrait of Miyanohara Ken in his studio.

On a day in March of the 44th year of the Showa era, despite being our first meeting, both Miyanohara and his wife warmly welcomed me, and the recording of our conversation proceeded smoothly. Despite his esteemed position as a master,Miyanohara exhibited a truly sincere and humble yet quietly lonely demeanor. Since then, Miyanohara's ceramics have become a precious treasure in my heart, like a refreshing breeze. Though not overtly expressed, the acceptance of life through Buddhist faith in "resignation" permeates beneath the surface. The artistic qualities of a temperament that must have been intensely sensitive and emotional, typical of an artist, transformed into a consistent assertion of high spirituality supported by Buddhist philosophy throughout his life.Miyanohara reflected on it in the following way:

"As I've mentioned before, I didn't enter this path because I liked it. However, now I devote my life to inlay and polychrome. Anyone can do at least the same or better work than I do. The key is not to succumb to failure, endure the low probability of success, and diligently persist with patience. (From the author's book 'Dialogues with Ceramic Artists,' Volume 2, Page 77; 拙著”陶芸家との対話”下巻77頁)"

The Artist’s activity in the "Tohto-kai" (Society of Eastern Ceramic Artists)

Miyanohara was born in Kagoshima Prefecture in the 31st year of the Meiji era (1898) and moved to Tokyo with his family around the age of seven. Raised in an affluent household with his father, a high-ranking official at a bank, he attended Aoyama Elementary School and then Aso Junior High School before enrolling in the Department of Architecture at Waseda University. Due to health issues, he had to withdraw from school. Around the first year of the Showa era, he studied Japanese painting under Tamon Yamanouchi and received teachings on Indian philosophy from Okakura Tenshin (the younger brother of Okakura Kakuzo, an English scholar).

Because his father was acquainted with Miyagawa Kozan (the second), Miyanohara was instructed to commute daily from the Meguro residence to the Miyagawa studio in Yokohama, following his father's "orders" due to their close relationship. At the age of twenty-nine, he began his journey in ceramics, entering the field later in life.

He recalled (from the same book): "It's probably because of my weak character. However, I thought that everyone could do something with their lives in the end. What never wavered was thanks to Okakura-sensei."

After about a year of assisting with various tasks and pottery at Miyagawa Kozan's studio, he was generously given a house and his own kiln at the Meguro residence by his father. The first Miyagawa Kozan originated from Kyoto's Mokuzei, establishing a kiln in Nantaida, Yokohama, actively exporting ceramics. He achieved great success as an artist, winning awards at international expositions and domestic exhibitions, ultimately becoming the first recipient of the Imperial Art Craftsman Award. The second generation, his nephew, assisted the first generation's work from an early age, excelling in skill and being recognized as a leading expert in the Kanto region during the Taisho period. Kyoto, at that time, boasted a prominent position in ceramics, with artists like Kiyomizu Rokubei (Rokubei VI), Miyanaga Tozan, Ito Tozan, Suwa Sozan, and Kawamura Seizan competing, making it a Mecca for ceramics.

In 1927, the 8th Imperial Exhibition fulfilled the long-standing desire of craftsmen by establishing the Craft Section as the 4th Division, inviting ceramic works from all over Japan. The Craft Section's inaugural exhibition marked the beginning of the Imperial Exhibition's role as a central force in Japan's ceramic community. In the same year, the "Toh-To-Kai" was formed, consisting of ceramic artists residing in the Kanto region including Miyanohara himself. Under the guidance of Itaya Hozan, Miyagawa Kozan, and Numata Kazumasa as advisors, artists such as Miyanohara, Omori Mitsuhiko, Dohi Tozan, and Yasuhara Yoshiaki (Kimei) gathered.

Kanto did not have high-quality clay, and the conditions as a pottery-making region were not ideal. However, lacking the traditional heritage of ceramics worked to their advantage. Miyanohara, being a broad-minded person under the mentorship of the tolerant Miyagawa Kozan, even ventured into the studio of his perceived rival, the famed Itaya Hazan, at the suggestion of Kozan. This exploration allowed him to present works based on a new, free, and experimental sensibility on the stage of Toh-To-Kai, devoting himself to pottery.

In 1929, at the 3rd Imperial Exhibition, he submitted a "Red Iron Crystal Bamboo-patterned Vase," earning him a selection. In 1931, at the Imperial Exhibition, he exhibited a "Wall-mounted Lighting Galaxy," receiving a special selection. Following that, in 1932, at the Imperial Exhibition, he submitted a "Glaze Inlay Cross-patterned Vase," again earning a special selection. In 1932, at the age of 33, with the introduction of Okakura Yoshisaburo, he entered into a "Kannon Marriage" with Hatsuko Yagihara. Despite societal expectations, Miyanohara and his wife maintained a harmonious family life, raising two sons and two daughters. She not only excelled as a supportive partner but also as his best assistant, cooperating with Miyanohara's kiln techniques throughout their lives.

The Imperial Exhibition transformed into the Bunten, and after the war, it became “Nitten.” Miyanohara was active on the Nitten stage, and after the war, he built a kiln at the current location in Matsudo. In 1956 (at the age of 58), at the 22nd Nitten, he submitted an "Inlay Ground Black Glaze Vase," showcasing his excellent inlay technique and sharp modern design sense, earning him the Japan Art Academy Award. In 1963, following the passing of the ceramic master Itaya Hozan, Miyanohara became the leader of the "Toh-To-Kai," guiding the next generation. Miyanohara’s rise to becoming a member of the Art Academy from the Nitten had an unspoken hierarchy that placed members above non-members. This hierarchical structure, combined with factors beyond the excellence of artworks, created an inescapable disadvantage, emphasizing the importance of networking.

Even though it was anticipated Miyanohara would be pushed into becoming an Art Academy member from the Nitten due to social conventions, he departed from the world without succumbing to the pressure, maintaining a transcendental and independent spirit. While it is regrettable, it can be seen as a characteristic and refreshing way of living true to himself.

執念の彩磁象嵌の大成: The culmination of Miyanohara’s tenacious commitment to the colorful ceramic inlay techniques

The style of Miyanohara ceramics is finely detailed and elegant. Following the rigorous discipline of his master, Itaya Hazan, he engaged in orthodox and earnest porcelain work. Derived from his personality, an inherent dignity emerged as a refreshing individuality. He remarked:

"I often tell young people, the twenties are the most crucial time. In my twenties, I was mainly drawing blueprints. Even now, I can't get away from drawing blueprints" (from the same book).

Miyanohara's colored inlay was born out of his experiences as a woodcarver. Just as he could not part from woodcarving, he explained it was similar to his inability to distance himself from architecture. His works inevitably took on the initial planned form. His ceramics are like the pottery of an architect. Although considered overly meticulous and not particularly interesting, Miyanohara's colored inlay differed in technique from Itaya Hazan.

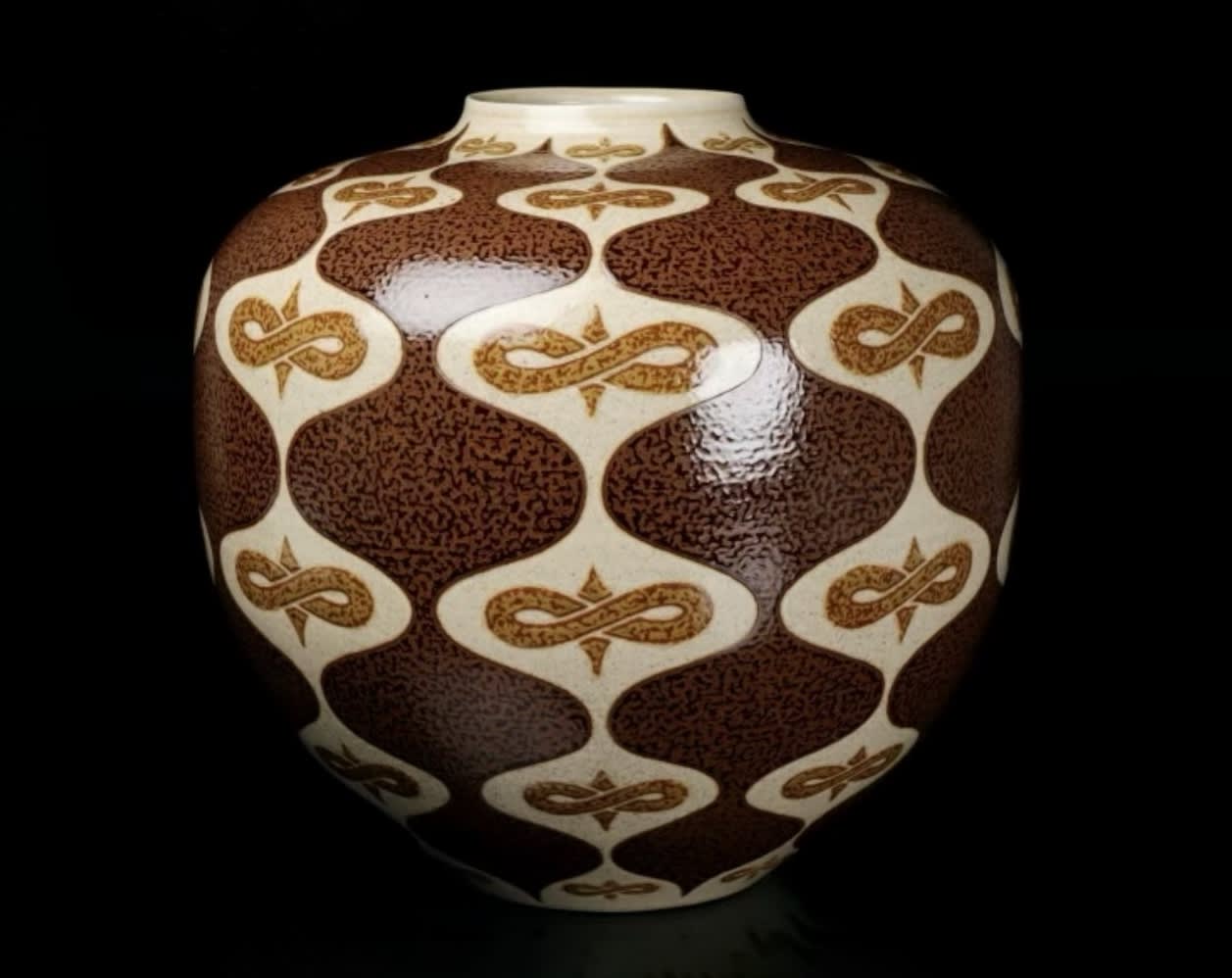

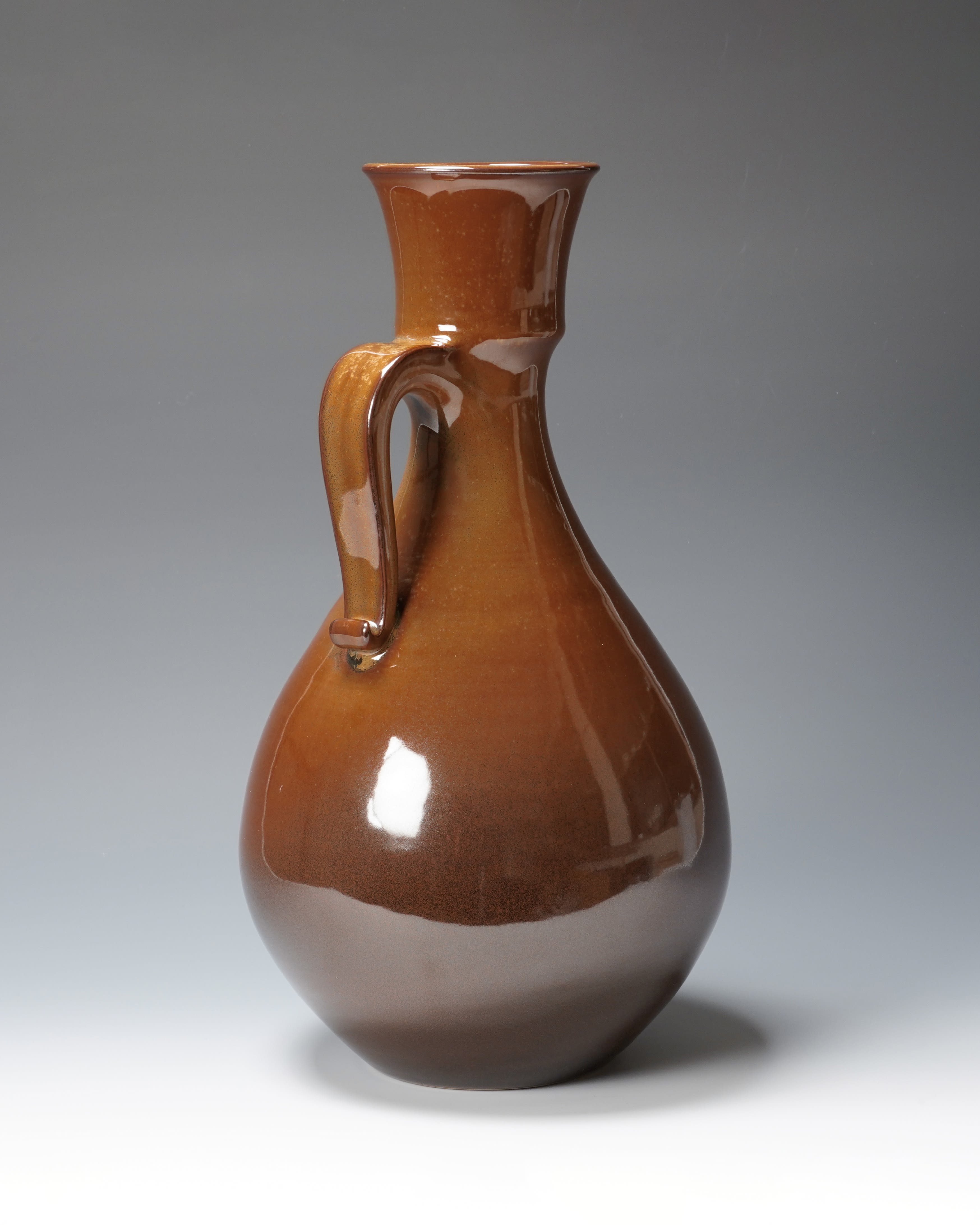

Miyanohara Ken, vessel, private collection. Contact us for price & availability.

In Itaya Hazan's case, he used a potter's wheel to turn the body while it was still soft, carving all the patterns in relief. After bisque firing, Itaya meticulously applied colors with Japanese pigments to the patterns, then applied a glaze before the final firing. In contrast, Miyanohara's colored inlay involved applying layers of color-engobe, with pigments, to the still-drying body turned on the wheel. To avoid cracking, he repeated the application several times (about seven times), allowing it to dry between each layer. It was an incredibly patient process. Afterward, he bisque-fired the piece, applied glaze, and fired it at high temperatures. The technique of applying colored clay under the glaze was briefly attempted by Itaya Hozan as well. However, it was only after Miyanohara took up the challenge, refined his skills, and finally succeeded, that this technique reached its full potential.

Itaya Hazan (1872-1963), Vase with Low-Relief decoration of Bamboo Leaves, ca. 1915, porcelain, colored slip, overglaze enamel. Image credit: The Walters Art Museum.

Today, Kusube Yaichi (1897-1984)'s "Saien technique'' is well-known for a similar method. Kusube 's method involves applying layers of color-engobe to the still-drying body, with the technique being the same. The difference lies in the type of pigments used: Kusube uses Western pigments, while the lineage of Itaya Hazan and Miyanohara uses Japanese pigments. The color sense of Kusube's works appears somewhat vivid, while Miyanohara's works give a feeling of more subtle hues. With this technique of applying color-engobe under the glaze, Miyanohara researched various ways to express colors, meticulously using light blue, pink, yellow, and other shades of color depending on the density in accordance with the patterns.

His refined and elegant designs were exceptionally dense. In comparison to Hazan's colored inlay, everything was calm and controlled. Perhaps, this modern sensibility stemmed from the difference in eras. Miyanohara's unique solitude and purity of heart seemed to permeate his colored inlay the most. Another crucial theme in his work was inlay. Inlay involves carving intersecting patterns into the soft body, embedding different clays to reveal the design, then applying glaze and firing.

This method developed in Goryeo into inlay celadon, becoming Samma in the Joseon period before being transmitted to Japan. This technique, absent in China or Europe, piqued Miyanohara's interest from his background in architecture, envisioning the world's best inlay. Like colored inlay, this was a highly technical and patient job, with subtle differences in the shrinkage of different clays, making the failure rate high. Both inlay and colored inlay heavily relied on patterns, and Miyanohara's designs were meticulous drawings based on detailed sketches. His floral-themed works were particularly notable. Even with detailed sketches, unnecessary parts were thoroughly omitted, elevated to a composed pattern. Although his works had a sketch-like appearance, they lacked a raw, painterly quality, appearing simple and cohesive.

Miyanohara Ken, celadon vessel, private collection. Contact us for price & availability.

Motifs of camellias and flowers were used to capture clear and concise patterns, exuding a scholarly sensibility. Miyanohara turned his attention to the Middle East, visiting twice after crossing his mid-sixties. During these visits, he depicted the distinctive round roofs of mosque temples as patterns, introducing bold curved patterns that were not seen in traditional pottery designs. These undulating curves, carved with thin, parallel lines, created a mysterious tonal gradation between abandon and precision.

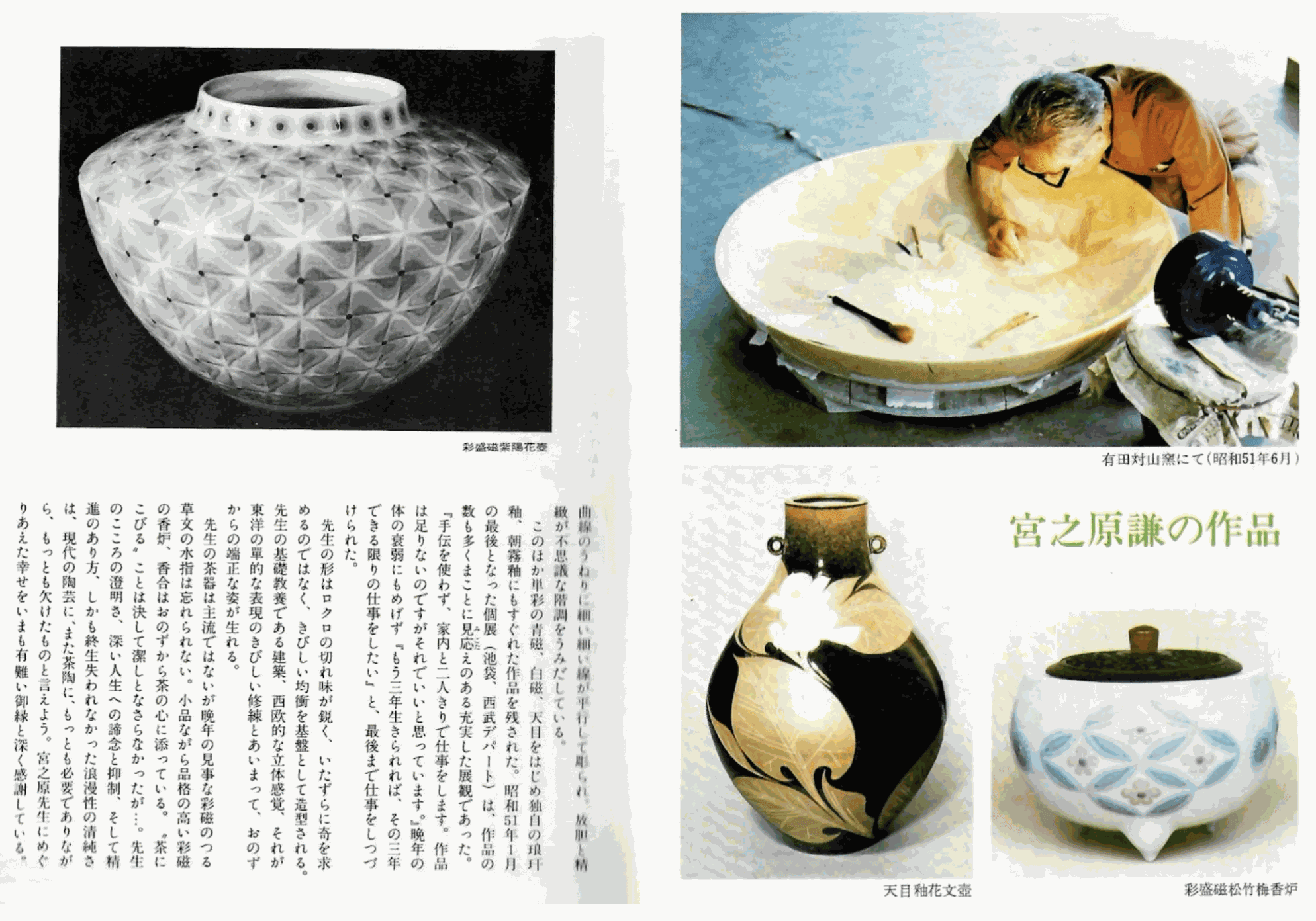

Additionally, he left behind excellent works, including monochrome celadon, white porcelain, unique langyao, and asagiri glazes. The last solo exhibition in January of 1976 at Ikebukuro, Seibu Department Store, featured a significant number of works, offering a truly impressive and fulfilling exhibition. Despite his declining health in his later years, Miyanohara continued working without assistance. He expressed,

"I work alone with my wife without using any help. Although there isn't enough work, I think it's fine."

Miyanohara Ken, Shu-Tenmoku Jar, private collection. Image credit: Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd.

Miyanohara's forms were sharp on the potter's wheel, not seeking whimsy for its own sake, but rather, creating models based on a strict balance. His foundational education in architecture, Western spatial sense, combined with rigorous training in Eastern monistic expression, naturally produced an elegant figure. While his tea utensils were not mainstream, the water jug with a creeping grass pattern in the final years of his remarkable colored inlay remains unforgettable. The small yet dignified incense burner and incense container in colored inlay naturally complement the spirit of tea.

“Miyanohara's clarity of heart, deep resignation and restraint toward life, and the way of devotion, coupled with an enduring romantic purity, could be said to be the most necessary yet lacking elements in contemporary ceramics, particularly in tea ceramics. I deeply appreciate the happiness of having crossed paths with Miyanohara."

English Translation by Dai Ichi Arts, Ltd., Kristie Lui, Haruka Miyazaki

株式会社 里文出版 Ribun publishing company

目の眼 ー古美術・民芸の月刊誌 11月号 昭和54年11月1日発行

Eye of the Eye ーMonthly Magazine of Antique art and Mingei, November issue Published on November 1, 1978