Translated transcription of Yasuhara Kimei’s writings on Kiln firing, 1950s

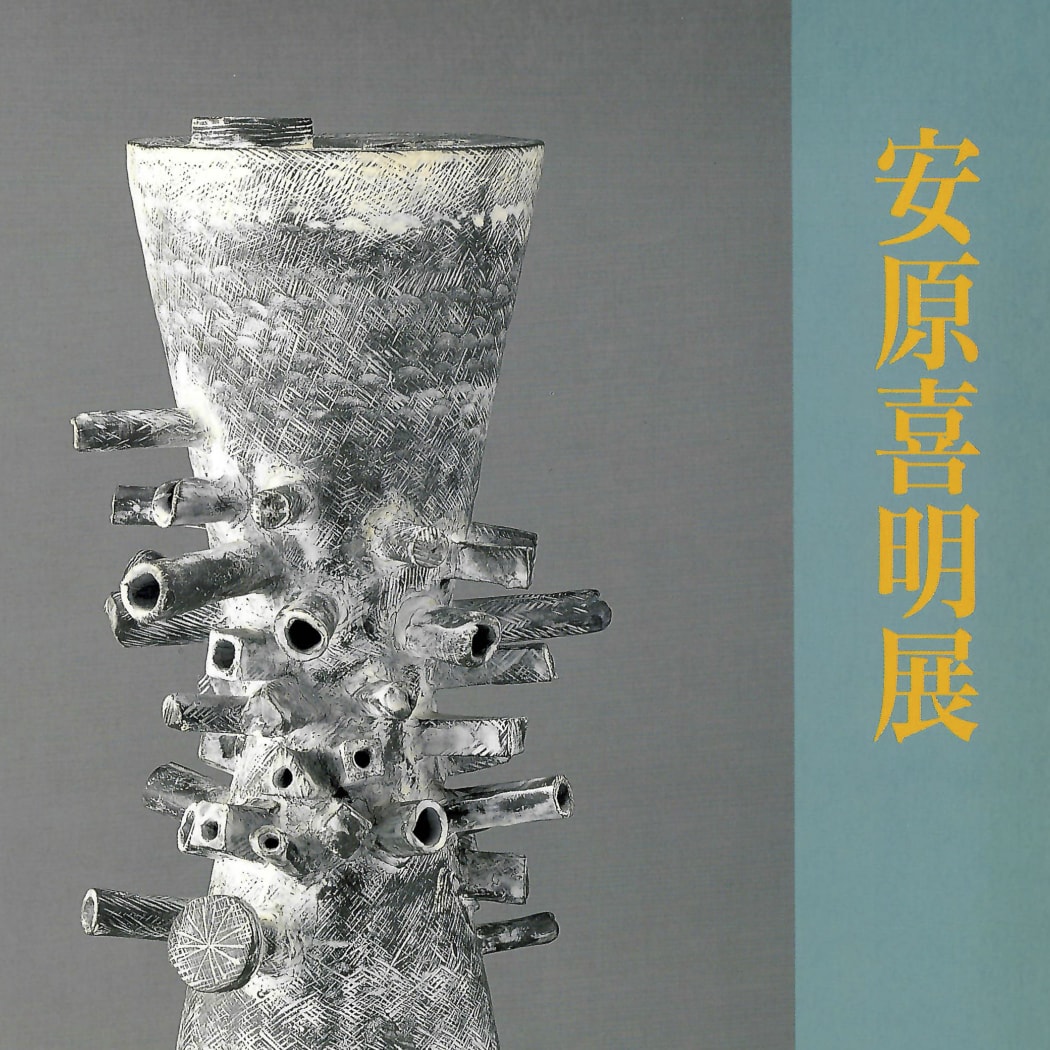

Published in Meguro Museum of Art, Yasuhara Kimei Exhibition catalog, 1993

Kilnside thoughts at night

Stoneware is a pottery technique that emerged following earthenware, originating from ancient times during China's Han Dynasty, and it was also used in Korea's Silla Kingdom and Japan, particularly in areas like Ibe, Bizen, and Shudei-yaki. Stoneware is named so because its raw material becomes somewhat glassy and, when broken, it has a hard, stone-like texture.

Unlike earthenware, stoneware does not absorb water, which makes it suitable for ceremonial and everyday use. However, with the discovery of glazing techniques, glazed pottery took the spotlight, and stoneware is now primarily used for high-quality traditional shrine utensils and has become less common as everyday items.

You can still find many old stoneware pieces used for rituals or burial items. Within the rich, earthy texture of stoneware, there lies a sense of profound beauty, creativity, intricate patterns, and refined elegance. Stoneware tells romantic tales of the past that you might not know unless you're familiar with it, and this sense of nostalgia and gentleness is quite captivating.

I dream of revisiting and reassembling these forgotten stoneware pieces with a modern sensibility, believing that something beautiful can be created once again through this process. I am eager to conduct extensive research in this field.

The term for the device used for firing pottery is called a "kiln."

When humanity first emerged in this world and felt the need for utensils, they initially used stones, and then they discovered the art of firing pottery. At that time, of course, they did not yet think about kilns. They simply stacked pottery on the earth's surface and covered it with burning wood, resulting in a very imperfect firing process.

If you look at the pottery from that time, you can see areas that are charred black, others that are strongly reddish-brown, and some that are smoked with oil, so there are hardly any uniform areas; it's mostly speckled due to the uneven firing.

Later on, they considered digging into the ground and firing pottery in a pit. However, with this method, the upper layers would be over-fired while the lower layers remained under-fired. Additionally, they couldn't control the firing temperature gradually, as we do today. Consequently, there were many failures, and the process remained imperfect.

Through various trials and errors, they eventually came up with the idea of covering something over the pit, allowing for a sort of steaming during firing.

At that time, perhaps because they still led a cave-dwelling life, they dug horizontal caves into the mountainside and created a pathway similar to a buried stoking hole in the back of the cave. This seems to be the initial concept of what we now call a charcoal kiln.

This particular design still exists today in a few places, such as kiln remains in old pottery regions like Seto, Tanba, and Ibe.

For instance, the kiln remains of Fujishiro in Seto had already developed considerably during that era, with high firing temperatures. They chose a hill of refractory clay and built pit kilns, resulting in fewer speckles in the pottery due to more even firing, higher temperatures, and better control of the firing process. This advancement marked a turning point in the art of pottery. During this time, they began firing items resembling both earthenware and stoneware.

However, there were still imperfections, such as uneven firings and fragility. To address this, they started constructing kilns on sloped hillsides. The design resembled the larger side of a bird's-eye rice cake with the opening facing upwards, and the pathway leading upwards. Over time, this evolved into the multi-chamber climbing kilns used in places like Kyoto, Seto, and Kutani today.

After the Meiji era, due to the availability of cheaper fuel and convenience, Western-style coal-fired kilns became popular, and nowadays, most kilns, from large factories to small workshops, have adopted this Western style.

Now, everything I've mentioned so far is related to the natural evolution of kiln technology. China is often referred to as the origin of culture and literature, and if you look closely at the character for "kiln" (窯), you'll see that it is composed of the character for "sheep" (羊) on top, and underneath, the character for "fire" (火), forming the character for "kiln." This hints at the possibility that China also had cave dwellings in the past. There's a story I've read in a book where they say that once a sheep entered a cave, and they couldn't catch it. So, they tried to smoke it out by lighting a fire at the entrance, and in the end, they managed to catch it after it had been roasted. When they went inside the cave later, they found that the surrounding soil had hardened during the fire, which turned out to be convenient for firing pottery. This is one theory of how the pit kiln design came into existence and how the character for "kiln" was created.

Editor's Note:

In the original text, the characters within <炻> are represented as 〈石) and there is a footnote explaining that these characters denote "stone" and that the phrase "炻器の〈石)は火扉に 石です" is a clarification. Here, I have omitted the clarification and used <石> for clarity.